I was introduced to recoil at a young age. During my formative years, my home state of Ohio required that hunters carry shotguns loaded with slugs during the state’s firearm season, and that meant every elementary school kid who wanted to hunt whitetails needed to be able to handle the recoil of a 12- or 20-gauge slug gun. During my early teens I also shot a centerfire rifle for the first time, and that happened to be my grandfather’s 300 Weatherby Magnum elk rifle which, I must say, left quite an impression.

In the shooting and hunting landscape where I grew up, everything kicked, and that may be why I’m so averse to being beaten up by firearms today. I’ve switched from 12- to 20- and eventually 28-gauge shotguns for much of my upland hunting, and most of the hunting rifles I own today are 6mm or 6.5mm bullets, and nothing over 3,000 feet per second.

Am I a wimp? I’d like to think that I’m older and wiser, and certainly arms and ammunition have advanced in the last three decades as well. But recoil is still around, and it’s still the enemy of good shooting.

Recoil Realities

If you’re ever going to be able to handle recoil effectively, you must first learn that you can’t “beat” it. You can mitigate it, condition yourself to it, and train for it, but recoil will still exist and still impact your shooting. In a 1995 article on the subject, John Wootters, one of the greatest gun writers of his generation and a veteran of many hunts with hard-kicking rifles like the 416 Taylor, said that each of us flinches, even imperceptibly, with each shot. He offered another sage piece of advice in that article: never let a gun hurt you.

You see, there still exists an attitude that the best way to handle recoil is to simply suck it up and deal with it, to take the pummeling like a proper man and keep shooting until the ammunition runs dry. It turns out that’s not the case. We are all hard-wired to avoid pain, and flinching is the body’s way of protecting itself against pending injury. Your brain knows that turkey gun with 3-inch magnum loads is going to kick. It tenses the muscles at the moment of ignition and the bird runs away, leaving you wondering how you could possibly have missed a tom at 10 yards.

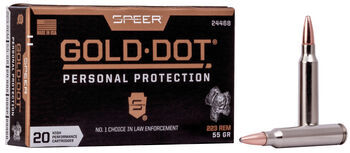

Gold Dot Rifle

Speer Gold Dot ammunition’s reliability has made it the No. 1 choice for law enforcement, and we offer the same performance for self-defense rifle applications. Gold Dot rifle is engineered to provide industry-leading performance in FBI protocol.

Buy NowThere are two different aspects to what we, as shooters, know collectively as “recoil.” There’s recoil force (also known as free recoil), which is quantifiable, and perceived recoil, which varies from one individual to the next. To help us deal with recoil and reduce flinching as much as humanly possible we’ll address each issue separately.

Beating Recoil Force

Recoil force is the number of foot-pounds of recoil a firearm generates. Most 22 LR rifles generate less than 1 foot-pound, which is barely perceptible. Most centerfire .22s like the 223 Rem. and 220 Swift generate around 5 pounds of free recoil. The 30-06 Sprg. and 7mm Rem. Magnum push with about 20 foot-pounds of force. Powerful magnums like the 375 H&H push 40 foot-pounds, and the real hard-kickers strike with more than 50. Shotguns range from about 10 pounds for a .410 3-inch load to 20 pounds for 12-gauge target or 20-gauge field loads, and they top 50 foot-pounds with magnum 12-gauge loads.

Free recoil is measurable, but it’s greatly impacted by gun weight. On an Argentina dove hunt, we scrambled to use 20-gauge guns instead of 12-gauge models, but after a few days I happened to switch and found, to my great surprise, that the 12-gauge guns had noticeably less recoil. The reason was gun weight. The 12-gauge ammo was loaded with 1/8-ounce more shot than the 20-gauge shells, but the guns themselves weighed more than a pound more than their 20-gauge counterparts.

Weight impacts free recoil in rifles the same way. A 5-pound hunting rifle is much more comfortable to carry than a 9-pound target rifle in the same caliber, but the heavy target gun will produce far less recoil.

There are, then, two obvious ways to reduce free recoil: shoot cartridges that produce less of it or add gun weight. For years, hunters wanted every cartridge to have the “magnum” moniker in the name, but what we’ve found over time is that moderate velocity rounds like the 6.5 Creedmoor are highly effective on game without the added pushback.

Perceived Recoil

Free recoil is measurable and quantifiable. Perceived recoil, by contrast, is more dependent on the shooter’s idea of pain and reaction to the noise and energy associated with shooting a firearm. I didn’t mention brakes in ways to reduce free recoil force, and that’s because I believe brakes belong in the perceived recoil section of this article. Muzzle brakes certainly do cut back on recoil by allowing gasses to escape, but they also substantially increase muzzle blast.

What’s wrong with that? Well, your brain doesn’t differentiate between a shove to the shoulder and a stabbing pain to the ears when it decides to flinch. Concussion and muzzle blast create flinches as fast (or faster, in my opinion) than free recoil. They’re also annoying and even dangerous to those around you. Guides hate them, and likely so does everyone else at your shooting range. Brakes work to reduce recoil, but you’ll have to decide if the stunning increase in muzzle blast is worthwhile. To me, it isn’t.

If you’re looking for an alternative to muzzle brakes, suppressors are a good option. They add weight to the muzzle and substantially decrease muzzle blast and noise. I never had any interest in owning a suppressor until I shot with one, and now most of my hunting rifles have suppressors. The downside, of course, is considerable paperwork and wait time when you apply for the tax stamp required to own a suppressor.

Shooting position is an important consideration when shooting hard-kicking guns. Shooting a hard-recoiling rifle from the bench or the prone position is challenging, and recoil fatigue will develop quickly. If I’m shooting hard-kicking rifles (anything from 40 foot-pounds and up) I prefer to zero from shooting sticks or, if possible, a standing bench. Standing benches allow you to firmly rest the rifle in position while standing to avoid compressing the body under recoil impact.

Impact Bullet

The Impact component bullet blends molecularly bonded construction and the Slipstream polymer tip for extreme accuracy, deep penetration at mid-range, and consistent low-velocity expansion at long distances.

Buy NowMonty Kalogeras, who runs Safari Shooting School in Texas, has a stand-up bench that consists of a round section of telephone pole held at chest height between two supports. The horizontal pole section is covered in carpet, and that’s where he has students sight in rifles such as the 500 Nitro Express and 458 Lott—hard-kickers to be sure.

Stock design and length of pull also impact perceived recoil. If you need to reach for the trigger or find yourself trying to operate a gun that is far too short for you, then perceived recoil will worsen. Many new shooters lift their head off the stock when firing, but the proper method is to develop a “cheek weld” and keep your face against the stock to prevent being slapped during recoil. Wearing gloves can help, especially when shooting handguns.

Lastly, and most importantly, you need to know your “when” while shooting a firearm. You’re only human and you will reach a point of diminishing returns, and probably more quickly than you’d like to admit. I understand that no one wants to stretch a one-day sight-in session over two days, but sometimes that’s what must be done to prevent the pain of recoil from impacting your shooting. Nobody likes recoil, but we must learn to live with it if you’re going to be a shooter or hunter. The secret is not to try and shrug off recoil but rather to control it and know your limitations. Know your limits and make sure that hunting and shooting remain enjoyable—even if that means hunting with a smaller caliber or gauge.