In the spring of 1986, FBI agents were searching for two notoriously violent bank robbers named Michael Platt and William Matix, and on the morning of April 11, agents in Miami spotted a stolen black Monte Carlo that was associated with the suspects and set out in pursuit. Three agent cars ran the Monte Carlo off the road, and immediately Platt and Matix opened fire with 357 Magnum handguns, a semi-automatic centerfire rifle, and a 12-gauge pump shotgun. Agents returned fire, and within seconds the quiet Miami street was turned into a terrifying maelstrom as bullets whistled through the air. Despite grievous wounds, FBI Special Agent Edmundo Mireles managed to shoot and kill both Platt and Matix, though the two suspects still shot seven FBI agents, killing two of them. Of the five surviving agents, three were seriously wounded.

The event was obviously a source of great pain to the family and friends of the agents who were killed. For its part, the FBI began to investigate the shooting to determine what the agents and the agency could have done differently. The officers involved fired several shots that hit Platt and Matix, but did not immediately stop the threat, which led the FBI to re-evaluate their choice of ammunition. In particular, they established a testing protocol to evaluate bullet performance.

FBI Testing Protocol

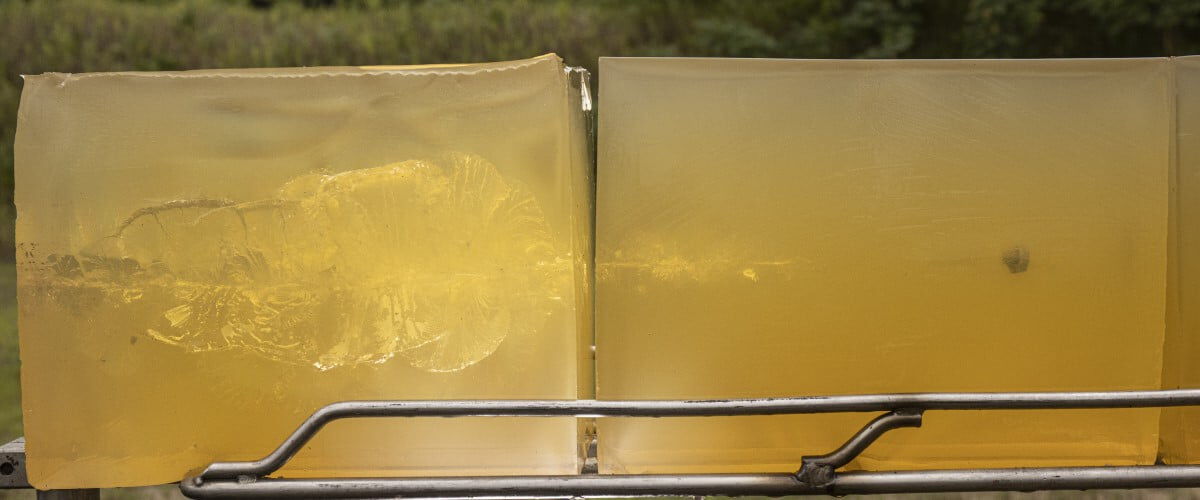

The FBI tests bullets in 10 percent gelatin blocks which are engineered to simulate human tissue. Test shots are fired into bare gel, and there are also a series of five “barrier” tests in which a bullet’s performance is evaluated in ballistic gel after having passed through different barriers. The five barriers tested are heavy winter clothing (four layers), ½-inch wallboard, two pieces of 20-gauge steel, ¾-inch plywood, and automobile glass.

Bullets are fired into bare gel and through the five barriers into gel from a range of 10 feet as part of the testing protocol. Bullets are tested for expansion and weight retention as well as penetration. Bullets that penetrate less than 12 inches are heavily penalized since they might not penetrate adequately. Likewise, bullets that penetrate more than 18 inches are penalized because of the risk of overpenetration; 14 to 16 inches of penetration is considered ideal.

With the FBI testing protocol in place, law enforcement agencies had a measurable standard against which to test bullet performance. This, in turn, allowed the FBI and other law enforcement agencies to select ammunition based upon standardized performance tests.

The Self-Defense Effect

FBI protocol testing is an effective method for law enforcement agencies to determine bullet performance, but it has also improved self-defense bullet designs. Bullet manufacturers began striving to develop projectiles that performed well in FBI protocol testing, and this required them to re-evaluate bullet design and construction and improve upon existing designs. Speer’s Gold Dot has performed extremely well in FBI protocol testing, thanks in part to a bonding between the jacket and core that prevents the two components from separating and promotes deep, straight-line penetration and high weight retention.

Gold Dot

Choose the bullet that set the standard. Our original Gold Dot line remains a benchmark for both self-defense and duty use, and it’s earned the trust of law enforcement world-wide.

Buy NowMost gun owners will never find themselves in a situation that requires them to shoot through steel or plywood, but the high standards set by FBI tests has ushered in a new era of advanced handgun bullet design. Interestingly, this new crop of bullets has also impacted cartridge performance. After the FBI shootout, the 9mm Luger was widely considered inadequate for immediately stopping a threat, leading it to be replaced by the 40 S&W. However, as bullet performance has improved as a byproduct of FBI protocol testing, current 9mm bullet designs have proven far more than adequate. The same improvements in bullet design have also enhanced the performance of the 38 Special, 380 Auto and other rounds widely considered marginal for defense. With well-designed defensive ammunition, these cartridge and many others are far more effective today than they were three decades ago.

What Do I Truly Need?

Thankfully, most of us will never need to shoot through barriers to defend ourselves, but that doesn’t mean the FBI’s protocol testing hasn’t impacted the lives of the average gun owner. The FBI protocol are measurable standards for bullet performance and inspire bullet manufacturers to closely evaluate the design and performance of their bullets. There’s ample evidence to demonstrate that bullets like Gold Dot will consistently perform in real-world scenarios. This has ushered in a new era of pistol bullet development and refinement from which we all benefit.

The FBI protocol test has impacted the industry in other ways as well. As a gun writer, when I write a feature on a new defense bullet, there’s an expectation from readers to provide ballistic gel testing results, which is a direct byproduct of widespread acceptance of the established FBI protocols. These evaluations have also opened the door for testing a variety of new bullets to determine how effectively they will perform in self-defense situations.

Perhaps the most important takeaway from FBI protocol testing, though, is that bullet performance is a critical component in self-defense. The FBI agents in Miami were well trained, and their bullets struck their attackers. However, that proved insufficient to immediately stop the threat. Gun owners still benefit from rigorous firearms training, but you simply cannot overlook the importance of bullet performance.